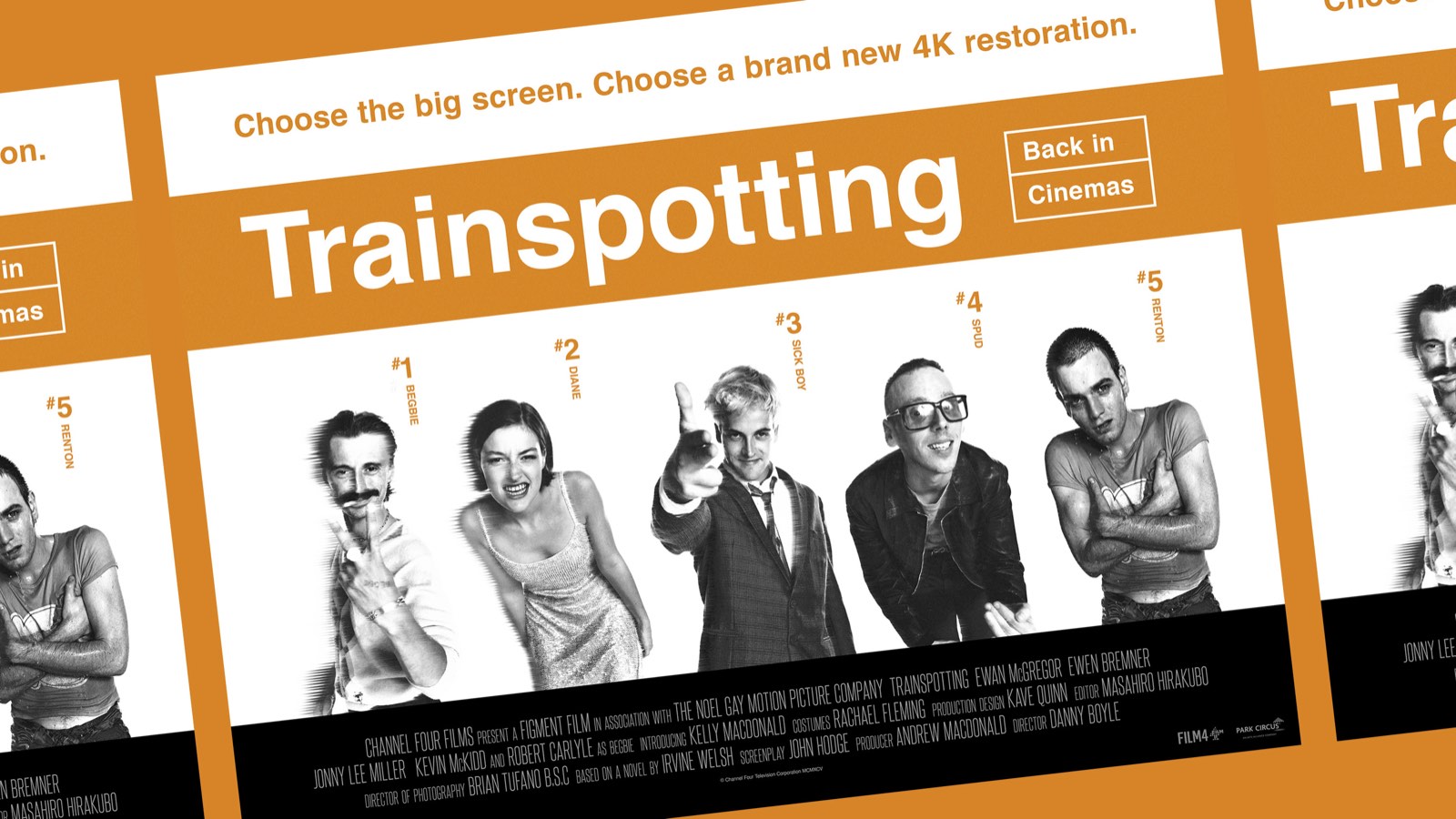

We are thrilled to be celebrating the safe reopening of cinemas and to support them in doing so, we are taking a dive into our catalogue for a closer look at what some iconic films and actors mean to all of us, and why.

Continuing our celebration of the centenary of the iconic Deborah Kerr, Sarah Street takes a closer look at her earlier career.

Deborah Kerr came to prominence in British cinema in a few short years from 1941 in Major Barbara to Black Narcissus (1947). Under contract with producer-director Gabriel Pascal she appeared at first in small, but distinctive roles, before stunning critics and audiences in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943). This drew her to the attention of Hollywood studios that were keen to sign British stars as part of their quest for quality. In the immediate post-war years they were keen to diversity their output, and British stars became important to the notion of ‘quality’ filmmaking. Kerr had begun to be frustrated in the UK, especially when Pascal didn’t seem to have a sense of direction for her career, and she ended up being loaned to different studios. By the end of 1944 Kerr was frustrated at what she perceived as a lull in her career. She wrote to a friend in Hollywood: ‘I am fed up with inactivity, fed up with the prospect of one rather mediocre (for Pascal) film which is all there seems to be in store for me in 1945. I have enough confidence in my abilities to push that I can be good if and when I get something to put my teeth into’.

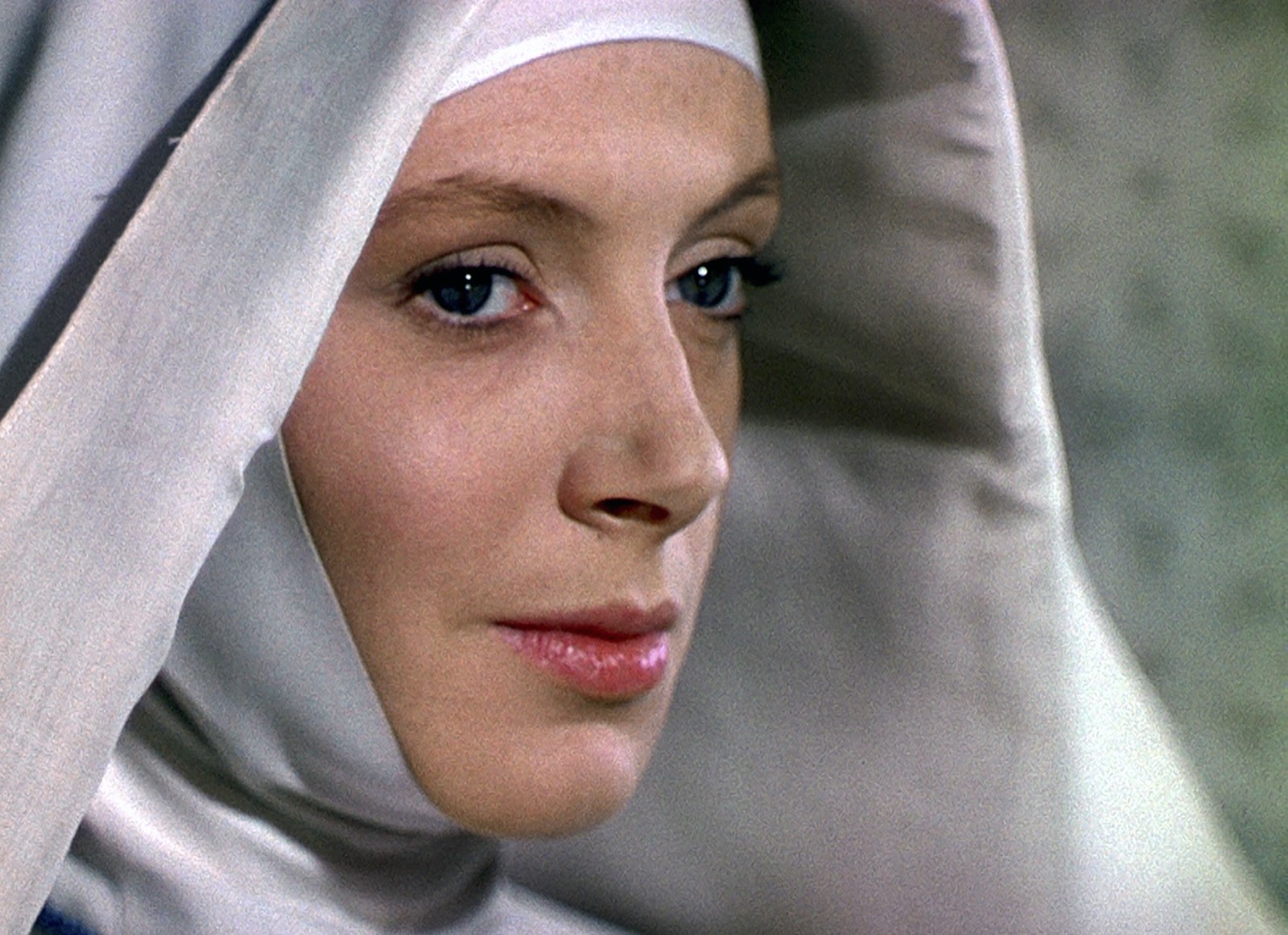

The role of Clodagh in Black Narcissus marked a seminal moment in Kerr’s career. She appeared on the cover of ‘Time’ Magazine on 10 February 1947 and that year won the New York critics’ Actress of the Year award.

Black Narcissus (1947)

When she made Black Narcissus, she’d already signed a 7-year contract with MGM, so Michael Powell had to bargain with Ben Goetz, head of MGM in Britain, so she could appear in the film. The first film she made for MGM was a co-production with London Films that was filmed in the UK: Perfect Strangers/Vacation from a Marriage (1945). Going to Hollywood at the end of 1946 was a highly significant move for Kerr. At the height of the studio system British actors were marketable commodities and those who migrated from successful careers in Britain were given opportunities to star alongside Hollywood’s best-known stars. Kerr’s contract with MGM stipulated that she would have star or co-star billing which automatically qualified her for a number of key roles. Kerr’s entrée wasn’t that of an unknown actress and her co-star status with major actors such as Clark Gable, Alan Ladd, Walter Pidgeon, Spencer Tracy and Cary Grant brought her to the attention of a broader screen public than had been possible in Britain. She also benefitted from MGM’s expertise such as the newly-contracted costume designer Irene, as well as from studio employees whose job it was to ensure stars had few practical problems on arrival from Britain. Kerr likened starting at MGM to being taken into ‘an enormous new boarding school’ with Louis B. Meyer like a ‘kind and avuncular’ headmaster.

Kerr’s early Hollywood films tend to be overshadowed by From Here to Eternity (1953) which came to represent Kerr’s frustration with her MGM contract, signalling a new direction in which she tried to break free from being typecast as a passive, well-bred ‘English Rose’. But it’s important to recognise that her post-From Here to Eternity career wouldn’t have been possible without some of the risks she was able to make within the MGM contract. Even though the films were variable, from the creative energy and risk associated with Edward, My Son (1948) to her minimal role in Julius Caesar (1953), Kerr’s first years in Hollywood were fundamentally important in establishing her as an international star.

Kerr’s Hollywood entrée coincided with MGM’s policy of bigger-budget, quality filmmaking and the studio’s expertise in costume design and Technicolor cinematography did much to enhance her physical presence as a star with a distinctive, photogenic appeal. From 1947-53 she appeared in twelve films, a record that demonstrated versatility in spite of her growing frustration in the early 1950s at the studio’s apparent reluctance to stretch her creatively as an actress. I want to highlight some of the roles that perhaps have been overlooked in assessments of her career, and that contributed much to her quest for versatility that characterised her post-1953 films.

In The Hucksters (1947) Kerr is paired with Clark Gable in a comic drama about New York’s Madison Avenue advertising business. Gable plays Vic, an advertising agent who meets Kay Dorrance (Deborah Kerr), a titled, war-widowed Englishwoman, when he is in pursuit of society figures to endorse a soap product in exchange for funds to help charities. When he calls at her New York townhouse Kay is dressed immaculately in a dark, tailored skirt to just below the knee and a white silk blouse with darker, ruffled edging down the front. She wears pearl earrings and her hair is styled softly back from her face, giving an overall impression of formality with a hint of softness because of the blouse, and breeding communicated by her accent, manners and posture that makes an instant impression on Vic whose reaction is very positive, even enraptured by her beauty. Yet despite this ‘proper’ beginning, the role of Kay develops towards the end of the film when she becomes more active, pursuing Vic by going out to Hollywood, taking risks and successfully competing with Ava Gardner for his love, with Vic and Kay emerging as the typical ‘special couple’ of Hollywood romantic comedy.

The Hucksters

Credit: Image courtesy of Sarah Street

If Winter Comes (1947) is set in an English village at the beginning of the Second World War. The role of Nona Tybar was relatively undemanding for Kerr, but she again gave a highly creditable performance that further established her foothold in Hollywood as a professional.

If Winter Comes (1947)

Credit: Image courtesy of Sarah Street

Edward, My Son was a completely different challenge from Kerr’s previous MGM films. It had been a very successful West End play in 1947 with Peggy Ashcroft and Robert Morley in the lead roles. These were replaced in the film by Deborah Kerr as Evelyn Boult and Spencer Tracy as her husband Arnold who is obsessed with giving their son Edward the best of everything at the cost of his friends, associates and eventually his wife. The film’s course through Edward’s life required Kerr to demonstrate Evelyn’s changed material circumstances, increasing personal anxieties and physical deterioration. She isn’t on screen for nearly as much time as co-star Spencer Tracy, but her performance showed a range and diversity that make the film stand out as remarkable. This can be seen particularly when Kerr depicts Evelyn’s decline as she turns to drink when her husband’s obsession with his son consumes him entirely. His business success has given Evelyn a life of plenty, yet she is depressed and desperate and by the end of the film she looks old and frail.

Edward, My Son (1949)

Credit: image courtesy of Sarah Street

Kerr was nominated for an Academy Award® for her performance as Evelyn in a role that required her to demonstrate many theatrically-inspired skills such as her work with voice, handling of objects, movement and gesture. She was far from the ‘English Rose’ assumed by many to be her defining persona and Edward, My Son remains one of her best performances for MGM. Kerr was dismissive of her other early MGM roles, feeling that Hollywood was ‘determined that this prim British lady should remain that way for ever and ever’, whereas the role of Evelyn was different: ‘an emotionally repressed woman…such women are real and vital and so are their problems’. In spite of the film’s importance in Kerr’s catalogue of distinguished performances Edward, My Son did poor business at the box office.

At the end of the 1940s MGM was managing to sustain the production of relatively expensive films, many shot in Technicolor. Part of the move to create cost efficiencies in the studio’s production and management operations involved the hiring of Dore Schary in 1948 as vice president in charge of production. Deborah Kerr’s next film was Schary’s idea, a very loose adaptation of H. Rider Haggard’s novel King Solomon’s Mines (1950). It was a completely new experience for Kerr, filmed in Technicolor for the first time since she left the UK. This showed her red hair and pale skin very obtrusively, recalling how colour enhanced her features in Powell and Pressburger’s films. Before they set out on their quest Elizabeth is shown as very beautiful, her red hair done up, red lips contrasted with the flesh tones of her skin, and wearing a pearl choker with matching earrings. The literal ‘undoing’ of the woman introduced at the beginning of the film creates a recurrent spectacle that is exploited by the cinematographer. After she decides she must cut her long hair which has become tangled, for example, we see her wash it in a pool near roaring rapids. Allan (Stewart Granger) sees her, lying on a rock, drying her hair and basking in the sun. This is filmed from a low-angled shot that emphasizes her beauty, the new short, curled hairstyle implausibly successful in terms of realism but perfect for celebrating Kerr as a film star.

King Solomon's Mines (1950)

Credit: image courtesy of Sarah Street

During these years Kerr was emerging as an actress associated with fashion. She wore gowns designed by important designers such as by Helen Rose in Dream Wife (1953). Rose was able to dress Kerr in costumes that exceeded the narrative demands of her role as a State Department diplomat. These ranged from tailored business suits to a glamorous halter neck evening gown with a full ‘New Look’ calf-length skirt which emphasized her slim waist. The film also showcased contemporary fashions for cocktail gowns and day dresses. In a very different role in Quo Vadis? (1951) Kerr appeared in a costume designed by Herschel McCoy. For the role of Lygia the costumes were a mixture of simplicity and splendour. When she’s taken against her will to the Emperor’s palace she’s forced to wear this blue dress adorned with a multitude of sparkling golden sequins and with gold braids crossed on the front to emphasise her breasts. She also wears long earrings with embedded turquoise stones and pearls that glimmer in the light and a heavy gold necklace threaded with pearls. Lygia’s hair is also laced with gold ribbon so that the ensemble fits in with the visual excesses of the palace’s mise-en-scène. But Lygia is in an environment she finds distasteful, so the clothes acquire ambivalent associations for the viewer: they present Kerr to us as a wondrous film star who looks stunning in an ostentatious costume of which her character most certainly does not approve.

Dream Wife (1953)

Credit: Image courtesy of Sarah Street

Quo Vadis (1951)

Credit: (c) WBEI 1951 - image courtesy of Sarah Street

Kerr next played Princess Flavia in The Prisoner of Zenda (1952). Walter Plunkett designed her magnificent, regal costumes. Even though the film is based on a late nineteenth-century novel, Flavia’s costumes echo the contemporary fashions of the New Look, with full skirts, tight waists and off the shoulder bodices.

The Prisoner of Zenda (1953)

Credit: Image courtesy of Sarah Street

Kerr’s appearance as Portia in Julius Caesar saw her onscreen for a very short time. It would appear that Kerr’s star billing was receding into respectable but unremarkable supporting roles, causing her frustration that led to her changing from being represented by agents at MCA to employing prominent Hollywood talent agent Bert Allenberg. He instigated a major breakthrough in her career by suggesting that she might test for the role of Karen Holmes in a screen adaptation of From Here to Eternity, the esteemed best-selling first novel by James Jones published in 1951, being planned by Harry Cohn at Columbia.

From Here to Eternity (1953)

Credit: Image courtesy of Sarah Street

At first sight the part of Karen wouldn’t be one that suggested Deborah Kerr’s name since Karen was a promiscuous married woman who has a passionate affair with a soldier in the same regiment as her husband. For Kerr the move symbolised a major rupture in how she was perceived in Hollywood. As she put it to the press: ‘There has to be a lady in Hollywood, but someone else can hold the lamp now. I’ve abdicated’. To be eligible to star in From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953) Kerr had to break her contract with MGM, she lost money and in exchange for her freedom to pursue other work in the theatre or with other studios she still had to agree to do three films for MGM in the future. After responding positively to Allenberg’s suggestion, Cohn asked the opinion of director Fred Zinnemann and producer Buddy Adler: both were struck by the idea as inspired casting. After a successful screen test the part was hers and her career entered a new phase in which her agency over casting decisions became much more apparent. But the extent to which she had cast off the association with being ‘a lady’ is questionable, since it seems from subsequent roles she was perhaps never able to banish it entirely from her persona. In fact, on close analysis even the part of Karen wasn’t completely out of character since despite the often shorthand description of her being a sexually rapacious woman, once her backstory was revealed she retained a quality of moral force with which Kerr had been associated in previous roles.

From Here to Eternity was a major box-office success, one of the highest ten grossing films of the 1950s. It won eight Academy Awards®, including for Best Picture and Best Director. Kerr was nominated for Best Actress but Audrey Hepburn won the award for her role in Roman Holiday (1953). Crucially, the film gave Kerr the profile she wanted: to show she could diversify and end a trend towards being typecast. This view was shared by the press in reviews including how Kerr would ‘astound picturegoers, most of whom must have dismissed her as one of those actresses who look well in still life, by the way she turns in a nifty study of a full-blooded young woman of seamy morals’. As she explained in an interview: ‘It enabled me to make the break without being vulgar’. It challenged her emerging persona to some extent while retaining aspects that the role of Karen couldn’t obliterate. The revelation of Karen’s past, for example, enabled Kerr to indicate depths to her character and a moral sensibility that disapproved of what she had been forced to become. At key points her lover Warden’s (Burt Lancaster) attitude towards her changes: when he visits her while Holmes is away and she first shows her vulnerability, and after the legendary seashore scene when she tells him her tragic history. With him we are encouraged to see deeper into Karen’s predicament, beyond the vamp she has been described as being by the soldiers. Much as Kerr’s casting forced audiences to reevaluate her persona as a star, the part of Karen also involved challenging dominant impressions. Yet Kerr also captures Karen’s physicality in her rapturous response to Warden on the shore, indicating pleasure in sexuality that is an important aspect of her as a contemporary American woman, particularly in the context of the film’s release in the early 1950s. The film also points at the double-standard many women were forced to accept whereby husbands could be unfaithful but not vice-versa. Kerr’s execution of the role was therefore brave, allowing her to subsequently pitch for similarly demanding roles that allowed her to deviate from what viewers might expect.

Starring in From Here to Eternity showed she had learned to negotiate the system, preferring selectivity and risk over the apparent haven offered by a long-term studio contract. Despite her own reservations, the early years at MGM had nevertheless given her a foundation from which to develop. The creative benefits of risk, epitomized by films such as Edward, My Son, made her receptive to change against the backdrop of a changing studio system and social climate.

In August 1953, after completing filming From Here to Eternity, Kerr left Hollywood for New York where she realised her ambition to combine her film career with stage appearances. Her first role was as Laura Reynolds in Robert Anderson’s play Tea and Sympathy (1956), to be directed by Elia Kazan on Broadway. As for many other film stars, particularly British, the desire to appear in theatre symbolized commitment to professional versatility as well as the development of skills required for live performance. The kudos of Broadway also conferred status that was often not accorded to film acting. In this sense Kerr was both returning to her roots while at the same time embarking on new challenges. She continued to work in Hollywood but took on diverse projects that further broadened her range and later filmed again in the UK. The twelve films she starred in from 1947 to 1953 provided her with a platform from which to develop as a performer, resulting in many more iconic roles, from An Affair to Remember (1957) to The Innocents (1961).

Sarah Street is Professor of Film and Foundation Chair of Drama at the University of Bristol. Her main areas of research activity are British cinema history, film genres, costume and cinema, set design and colour film.

Feeling inspired? Get in touch to book a season of Deborah Kerr films

To read more about Deborah Kerr, buy Sarah Street's book