We are thrilled to be celebrating Christmas with mostly-open cinemas, and so we're revisiting some of the most iconic films in our catalogue to examine what they mean to us all and why.

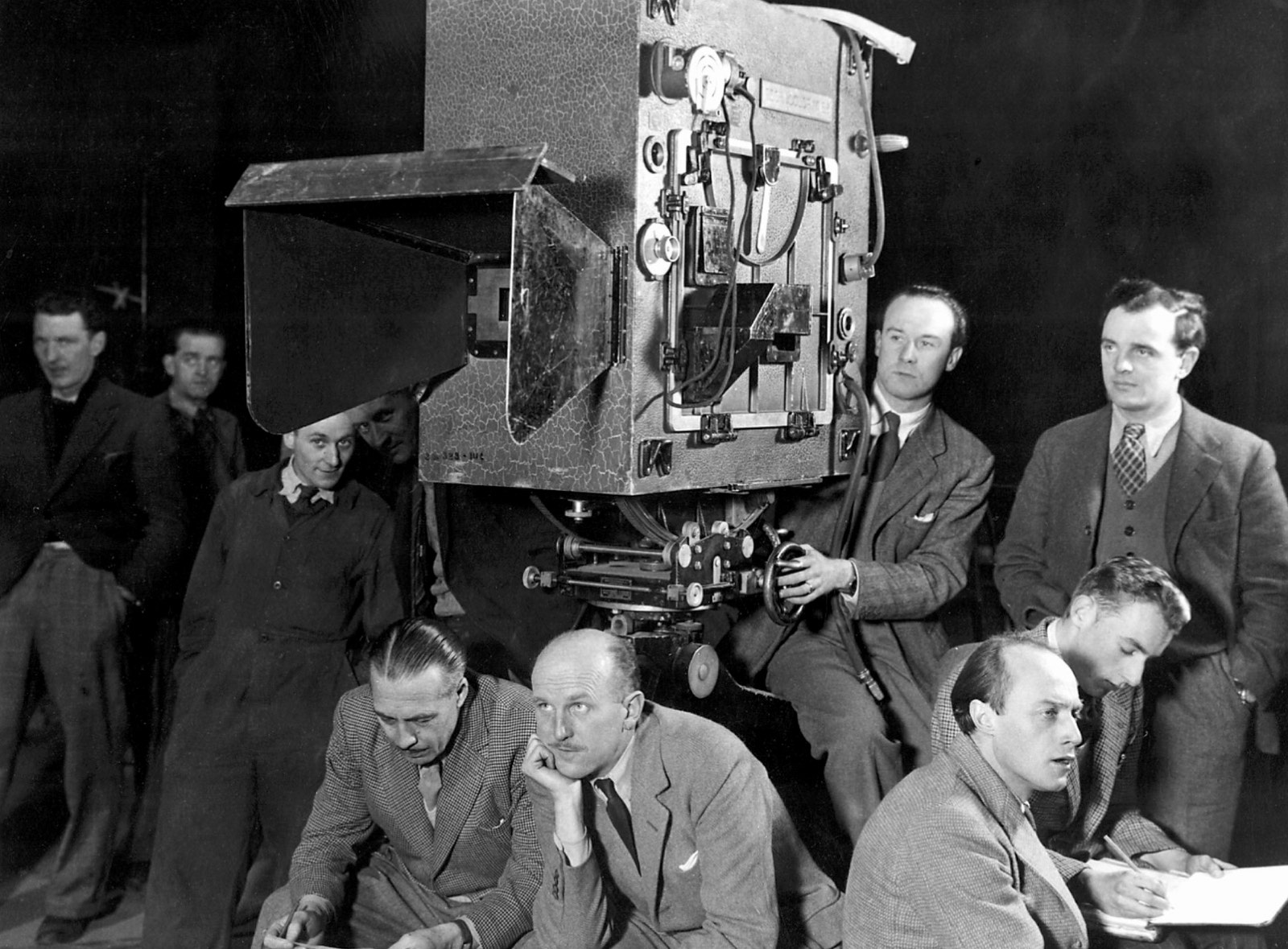

One of the most beloved British films ever made and the jewel in the crown of Powell and Pressburger’s prolific filmography, A Matter of Life and Death (1946) is perfect magical festive viewing and celebrates its 75th anniversary in 2021!

Here, Ian Christie takes a Close Up look at this stunning film. Ian wrote the BFI Classics book on A Matter of Life and Death, which will appear in a new edition next year.

He teaches film at Birkbeck College, and his 2019 lectures about the Powell-Pressburger partnership are available to view on the Gresham College website.His book Arrows of Desire: the Films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, with its original foreword by Martin Scorsese, is published by Faber.

"This is the universe. Big, isn’t it?" This must surely be one of the best opening lines of any film – casually spoken, but awe-inspiring, with what’s still an incredibly good 3D stellar model that looks even better with each new restoration. Right from the start, the film strikes an intimate note, even while it’s persuading us to contemplate the universe, the hereafter, and an epic love story that marks the end of World War Two. Yet Powell and Pressburger originally billed it as a ‘stratospheric joke’, no doubt to avoid any suggestion that this was yet another war film, when it appeared at the end of 1946.

And despite the ominous title it is full of irreverent humour. As a pilot’s fate hangs in the balance due to a celestial slip-up, his second in command hovers in what seems to be heaven’s waiting room, where wings are being handed out and a newly arrived American bomber crew heads straight for the convenient cola machine. When he exclaims ‘Holy smoke’, the angel-receptionist warns him: ‘we don’t call smoke holy here, because there’s no smoke without fire’. And perhaps the best joke of all was only added in the film’s post-production. When the heavenly Conductor magically appears on earth, surrounded by rhododendrons, he says ruefully, ‘One is starved for Technicolour up there’. But if you watch his lips carefully, it’s clear that Marius Goring actually said ‘one is starved for colour’ on set, and that this extra gag was dubbed in later.

I’ve been watching AMOLAD, as it’s known among Powell-Pressburger fans, for over fifty years, ever since first being amazed by it on a small television, through just about every film and video format, on screens small and large, right up to the latest superlative 4K restoration. And I keep discovering new facets of this extraordinarily ambitious work, as do many other enthusiasts. An American medical researcher has revealed that the film’s neurological basis – that Peter Carter is suffering from a specific form of brain damage – is extremely accurate and plausible, thanks to the father of Michael Powell’s wife having briefed him. And the same researcher has recently been able to tell me more about where Powell got the inspiration for the great Camera Obscura sequence, in which Dr Reeves surveys his village from above, creating a magnificent metaphor for how the whole film looks down on the world of 1946, linking medical science, philosophy and romance – with a great deal of classic English literature – in a wonderful fable for the post-war world.

I adopted AMOLAD as my own all-time favourite film many years ago – if you’re a film historian and critic, you have to have a ready answer to the inevitable question. And apparently it was Michael Powell’s favourite among his own films, bringing together his love of creating movie magic with his innate romanticism. The Powell-Pressburger films were almost forgotten during the 1960s and 70s , and were incredibly difficult to see during these decades, except on television.

I was privileged to help bring them back into circulation in the 1980s, when Michael and Emeric were able to see younger generations respond to their vision. Since then, it’s wonderful that video formats and restoration have allowed them to become some of the most admired of all British films. And that Park Circus now make many of them available for cinema screenings – which we all hope will soon return. The magic of The Archers’ films can survive in many formats, but can best be appreciated on a big screen - with an audience being invited to admire the size of the universe, and our small but vital place in it. Walter Scott is one of the poets quoted in the film:

Love rules the court, the camp, the grove, And men below, and saints above; For love is heaven, and heaven is love.