Raging Bull © 1980 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved. Images © 2022 The Criterion Collection. All Rights Reserved.

Park Circus is thrilled to bring Raging Bull back to cinemas worldwide from 14 April 2023 in an unrivalled new 4K restoration. In preparation, i paper lead film critic Christina Newland steps into the ring to explore the themes and complexities of Martin Scorsese's brutally uncompromising, visionary masterpiece.

When Martin Scorsese first embarked on his legendary collaboration with Robert De Niro to tell the loose biographical story of a disgraced middleweight boxing champion named Jake LaMotta, his initial attitude was surprising: ‘One sure thing was that it wouldn’t be a film about boxing. We didn’t know a thing about it and it didn’t interest us at all.’

That statement of indifference toward the blood sport which defined LaMotta - in the ring and out - might seem strangely recalcitrant given the final results of a film like Raging Bull. After all, it contains some of the most beautifully memorable fight sequences ever committed to celluloid, lensed by Michael Ballhaus and edited with Eisenstein-ian flair by Thelma Schoonmaker. It also depicts some of the major moments in mid-century boxing history, like the pivotal sequence of LaMotta’s bruising defeat at the hands of the ferocious Sugar Ray Robinson.

Our brand new artwork for Raging Bull

Yet Raging Bull is far from the realm of the traditional sports biopic. Its narrative, framed at the beginning and the end by an aged, bloated LaMotta’s reflection in a dressing-room mirror, allows Scorsese to address masculinity and violence - rather than the redemptive, rags-to-riches story to be expected from the life of an Italian-American born in the rough and tumble, mob-infested Bronx tenements of the early 20th century. It’s a film which contains no sense of real victory or success, in spite of any external trappings of athletic fame or upward mobility; LaMotta’s pursuit, ultimately, feels hollow. He alienates those closest to him - his brother/trainer Joey (Joe Pesci, in unforgettable form) and his wife Vickie (Cathy Moriarty) - through his obsessive, abusive jealousy: this is the story of a world champion who also happens to be a born loser.

All is not well in its world of gender relations: perhaps more than any other Scorsese film, it is a movie about masculinity at its worst. It unflinchingly depicts the shrunken, ugly machismo bred in cramped tenement neighbourhoods, without glory or any particular glamour. It’s telling that the film’s worst violence is frequently outside the ring, in Jake’s domestic life. The boxing crowds and matches are violent, but the Mafia-infiltrated Bronx neighbourhood Jake comes from suggests that violence is also a way of life: Jake asking Joey to punch him in the face; Joey’s vicious beating of Salvy (Frank Vincent) for being seen with Vickie; and Jake’s continuous violence towards Vickie herself, culminating in a punch that knocks her out.

Raging Bull © 1980 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved. Images © 2022 The Criterion Collection. All Rights Reserved.

There are many other instances of violence: Joey’s threats at the dinner table that he will poke his son’s eyes out if he doesn’t behave, swiftly followed by Jake storming in and beating Joey up over an imagined affair. Even when no one is pummelling in the ring or knocked out in their own kitchen, brutality is always close to the surface. In the first domestic scene of the film, Joey upturns a table after a disagreement with his first wife over the cooking of a steak. A neighbour downstairs shouts, “What’s going on up there, you animals?!” and Jake threatens to eat his dog, another relation to the animality of his character and the blood sport he engages in.

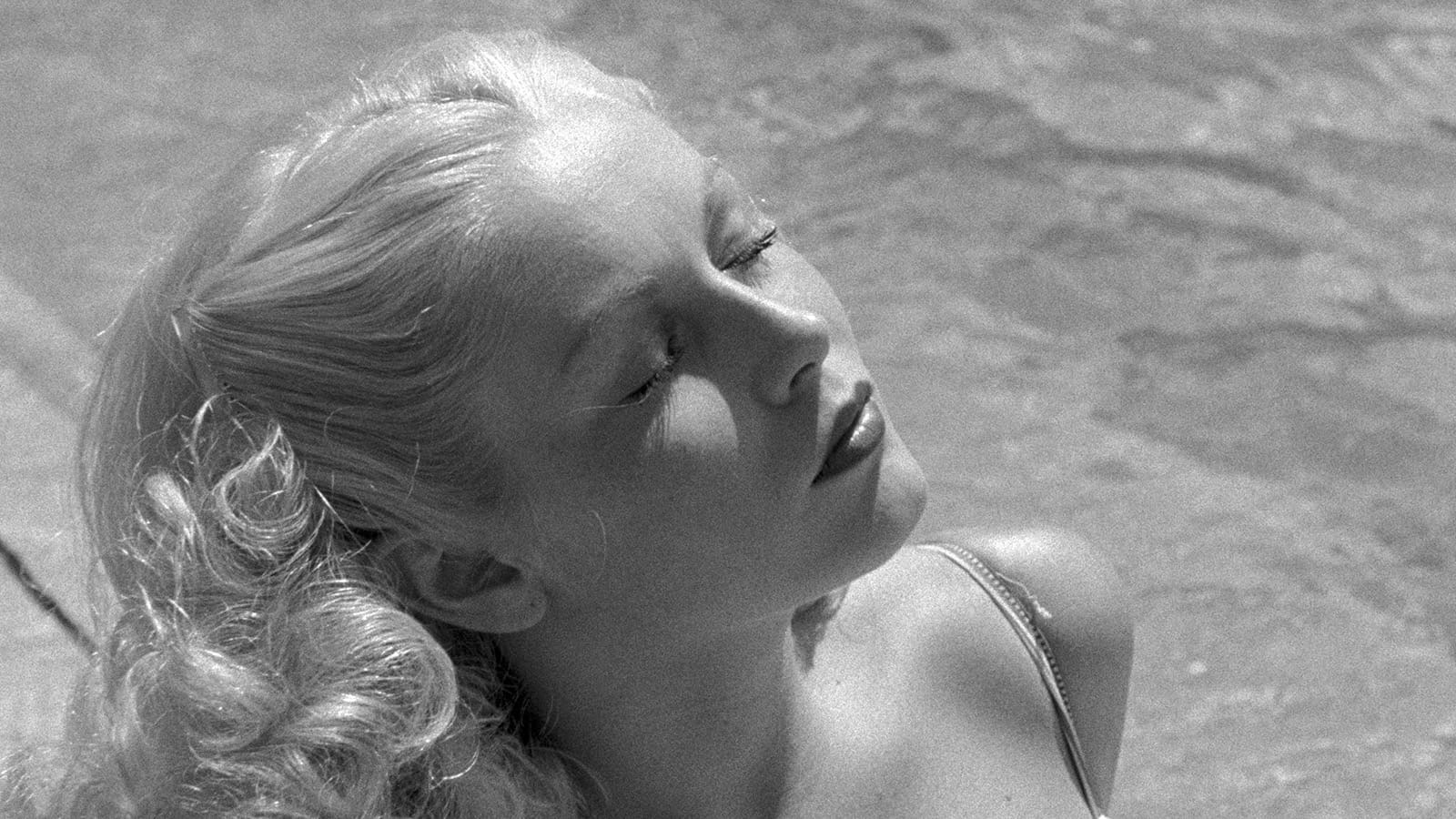

Domestic violence is another part of the world Scorsese depicts: LaMotta’s psychopathic sexual jealousy over Vickie – portrayed through his overwhelming desire to control her sexuality – leads him to bully, threaten and slap her throughout the film. Vickie is presented by Scorsese as an old-Hollywood style blonde siren, but one who is completely under Jake’s thumb. Dysfunctional male/female relationships are dealt with in many (if not most) of Scorsese’s films, but never so explicitly as in Raging Bull – particularly the ‘Madonna-whore complex’, a psychological tendency in certain men to distinguish women completely based on the dichotomy of either virginal, marriageable women or those only good for casual encounters. As a result, they become unable to continue functional relationships with the women they have sexual encounters with, believing the woman to have crossed over into the ‘whore’ category.

Raging Bull © 1980 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved. Images © 2022 The Criterion Collection. All Rights Reserved.

Jake’s sexual jealousy seems to run by this backward, misogynistic logic: now that he has had sex with Vickie, he believes that her sexuality is uncontrollable and this makes her potentially available to other men. This paranoia drives him far enough to accuse his own brother of having an affair with her. Scorsese also deals with these issues in one of his early films Who’s That Knocking at My Door? (1967): Joey and Jake’s attitudes do not exist in a vacuum, but are symptomatic of their cultural and social milieu – one that Scorsese himself emerged from. But beyond an uncomfortable relationship with women, Scorsese’s men struggle with themselves, with their cultural backgrounds, their religious guilt and the need to live lives predicated on macho violence. The masculinity crisis which leads to misdirected violence and sexual confusion is not only a burden to women, but extends toward other men as well.

LaMotta is a sexually confused bully who can only purge his psychotic impulses in the microcosm of a boxing ring and whose pugilistic career still cannot provide a buffer for his rage and self-destructiveness. Yet on a formal level, Raging Bull practically reinvented how boxing scenes could be shot and depicted, from the ring’s relative size diminishing or widening based on LaMotta’s success or lack thereof within it. Sweat and blood flies in slow motion from men’s brows; there are extreme close-ups, unusual point of view shots, flashing camera bulbs; the effect is stunning.

Ultimately, form and subject make Raging Bull something of a paradox: a film of balletic, strange visual poetry, with elegiac beauty written into its every shot; yet about a man of unmoving, ugly viciousness, pierced with rough Scorsesean street vernacular and a dark heart of broken macho ambition. The ring serves as both penance and justification for LaMotta’s wild behaviour; an arena where he can both primitively perform his gender and satisfy his inarticulate desire for self-punishment. Jake’s rage outside of the ring can only be purged inside of it, and as his impulses grow uglier, his so-called success story does too.

Download the programme notes

Raging Bull is back on the big screen worldwide from 14 April 2023 in a knockout new 4K restoration, approved by director Martin Scorsese. Find a screening here or get in touch for theatrical bookings.

Christina Newland is the lead film critic at the i paper and a journalist on film, pop culture, and boxing at VICE, Criterion, Sight & Sound, BBC, MUBI, Empire, and others. Find her on Twitter @christinalefou.