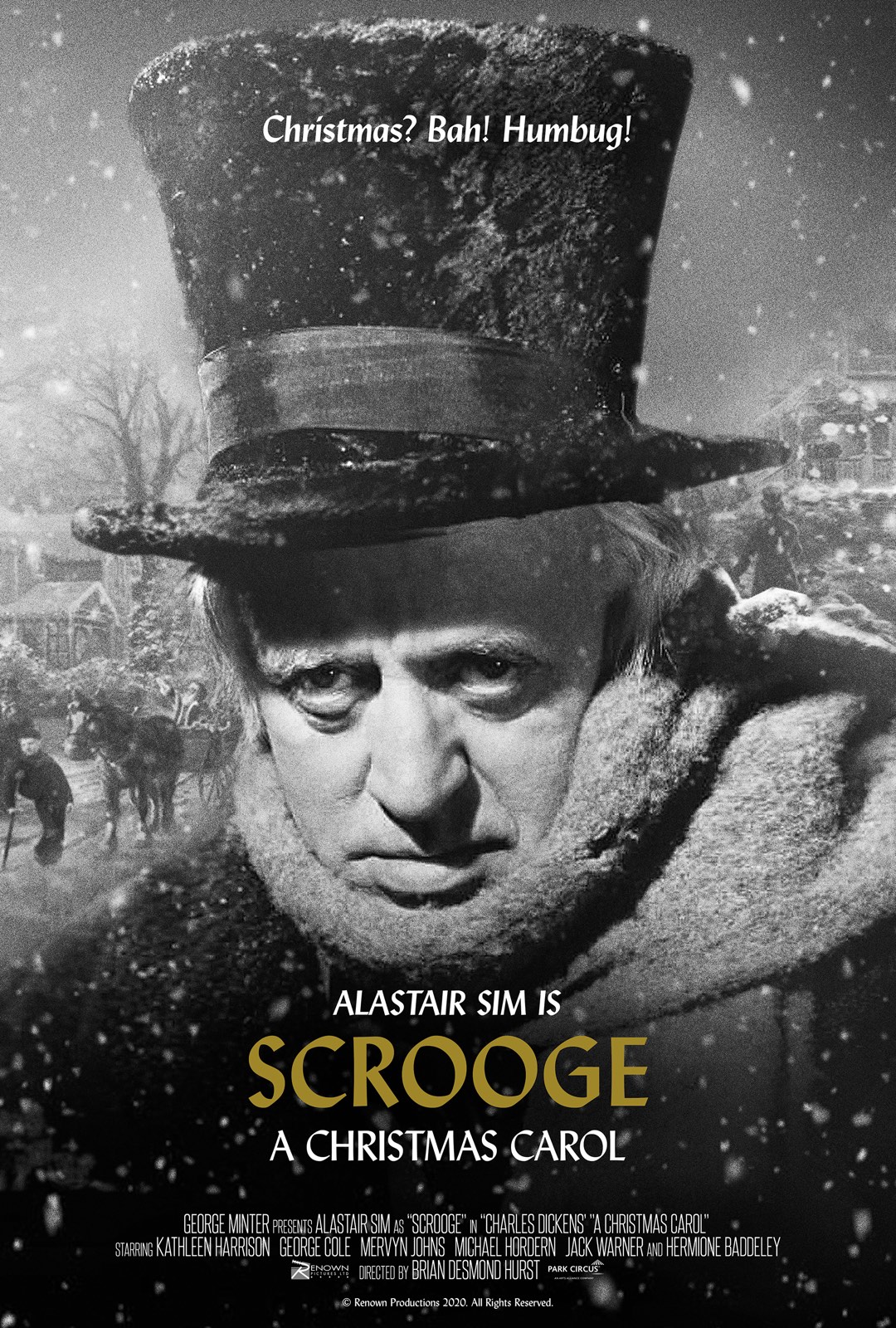

Newly created one-sheet for SCROOGE (1951).

Now it's November, we're going into full winter mode, and of course, Christmas is just around the corner, so we're looking forward to celebrating some of our favourite festive films.

We are revisiting one of our favourite Close Up pieces to get excited about the festive season - an examination of 1951 Christmas classic, Scrooge, with Brian McFarlane.

Brian is Honorary Associate Professor at Monash University, Australia. He is a distinguished figure in literature and film whose books include An Autobiography of British Cinema: As Told by the Filmmakers and Actors Who Made It (1997), Novel to Film: an Introduction to the Theory of Adaptation (1996), The Cinema of Britain and Ireland (2005) and The Encyclopedia of British Film (2011).

If Dickens had had an astute agent, his descendants would never have needed to work again. Well over four hundred films and television programmes have been derived from his work, and the list goes on and on. Even more amazing is the number adapted from A Christmas Carol across the media range – and indeed across national borders. At last count, since 2019, there were ten prospective versions either in release or in production or announced for production, the approaches (including animation, for instance) getting ever more imaginative.

So what accounts for the ongoing popularity of the novella and its protagonist Ebeneezer Scrooge, a surname that has no doubt passed into the language? The very name seems to evoke the bleak, mean-spirited, miserly businessman/money-lender who, following a night of other-world visitants, emerges transformed to the point when he says: "I am not the man I was". In the moral renewing of Scrooge, Dickens has shown what human possibilities are capable of.

Not having seen Brian Desmond-Hurst’s 1951 production of Scrooge for many years, I find that re-viewing it makes me wonder why we haven’t heard more about it. Perhaps its being made in the shadow of David Lean’s more ambitious and critically regarded Great Expectations (1947) and Oliver Twist (1948) led to its seeming more modest in scale and aspiration. However, on screen again nearly seventy years on, Scrooge in many ways seems at least their equal as it renders one of Dickens’ most loved works in potently cinematic terms.

Scrooge is not only wonderfully in tune with Dickens but also has a taut, visually arresting style as it moves between this and that place, between reality and fantasy. Scrooge’s substantial but grim abode and his clerk Bob Cratchit’s modestly confined family home with the warmth of its affections, or the lavish quarters of wealthy businessmen and the bleakness of snowy narrow streets and needy personnel: all are rendered with evocative precision in the cinematography of C.M. Pennington-Richards. There is a sense of 1940s film noir hovering over the black-and-white imagery that creates these different worlds and reinforces the contrasts of what life has dealt those who inhabit them.

When it comes to the fantasy of the three spectral figures that enter Scrooge’s Christmas Eve dreams (the Ghosts of Christmas Past and of Christmas Present and The Last of the Spirits), the photography and the editing, along with Richard Adinsell’s musical score, all work to persuade us that what looks like fantasy also helps us to see how he has become the austere figure is he but also the man he may still become. And of course Alastair Sim’s performance is riveting from start to finish: perhaps no actor was ever better able to suggest both the sinister and the comic in the one persona and Scrooge gives him one of his finest hours.

In fact, Dickens would surely have relished the film’s cast, replete as it is with dozens of those character players who were one of the glories of British cinema’s heyday. Not only Sim snarling, carping or leaping about ecstatically at the end, but such other names as Mervyn Johns (Cratchit), Hermione Baddeley (Mrs Cratchit), George Cole (the young Ebeneezer), Kathleen Harrison (Mrs Dilber), Jack Warner (Mr Jorkin) and many others ensure a truly Dickensian range of eccentricity, sharpness and poignancy.

Like the novel, but without slavish reverence towards it, the film lifts the spirit without becoming sentimental. It has earnt its way, as Scrooge himself has done, from his ‘Bah! Humbug’ dismissal of the Christmas spirit to Tiny Tim’s ‘God bless us, everyone’.

Book to see Scrooge at BFI Southbank, London this Christmas

Book Scrooge for your cinema this Christmas!